AUTOMATIC Identification System data is a favourite tool of risk and compliance professionals, but bad actors are routinely exploiting the reliance on this information by manipulating tracking data to show vessels in false locations when engaging in illicit or sanctioned trades.

The intentional altering of positional information by people on board or affiliated with the vessel in question is known as first-party spoofing.

This method allows a ship to appear in one place when it is really elsewhere, and typically engaging in sanctioned or other illicit activities.

It is a more advanced form of AIS manipulation than simply “going dark” because it leaves less of an obvious trace.

A gap in AIS transmissions is easily noticed. Alarm bells would be going off for many risk and compliance professionals if a vessel disabled its AIS for days while sailing in the Black Sea towards Russia, for example.

It takes extra vigilance, however, to capture and identify incidents of spoofing because the vessel will be continuing to transmit data and often does so in places that are entirely legitimate for it to be.

This begs the question: what are the red flags that people need to look out for when they’re trying to verify if a vessel’s positional data is legitimate?

Certain information is transmitted in a vessel’s AIS data, such as the ship’s identification numbers and name, as well as speed, draught, heading and course over ground.

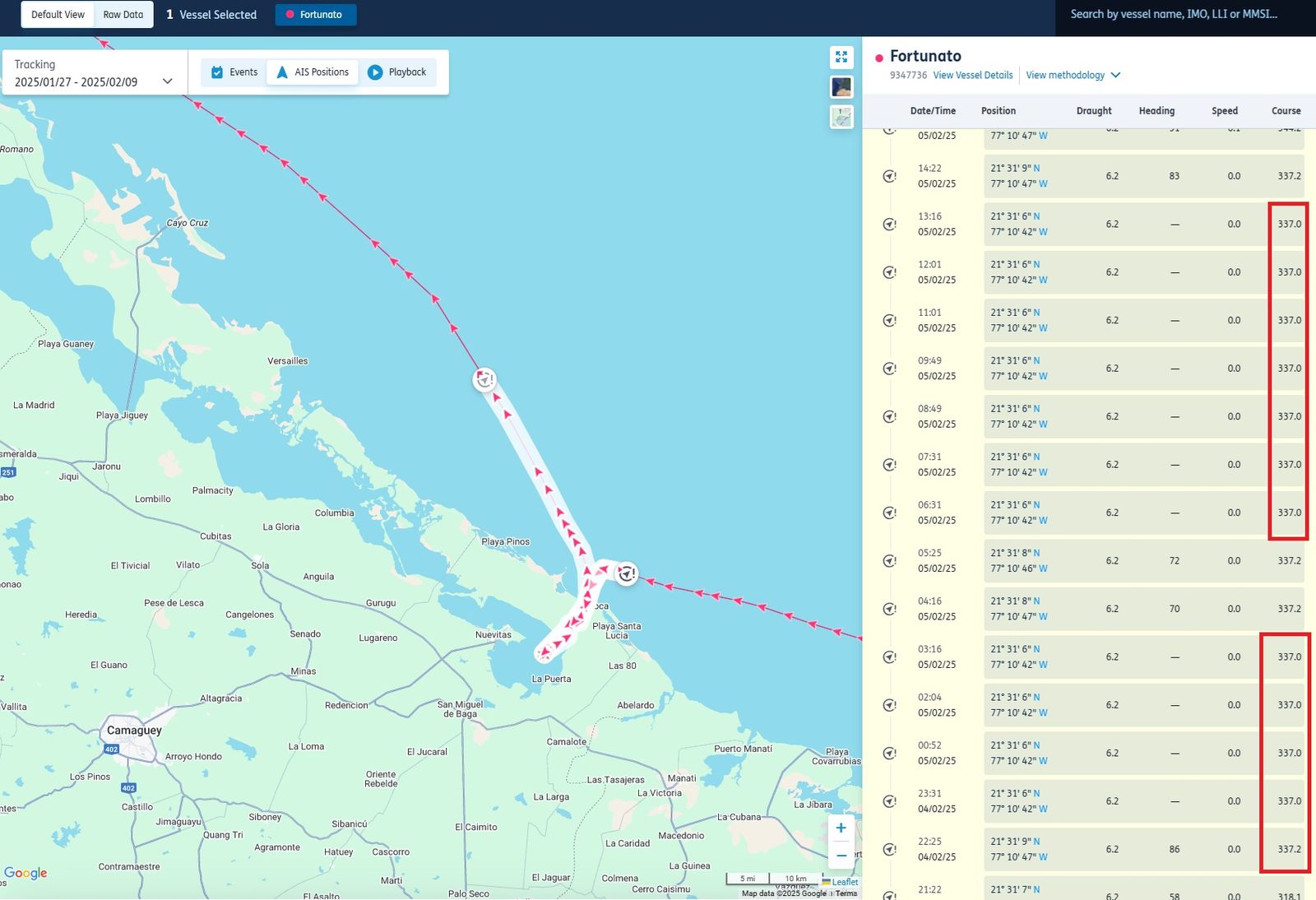

If there’s a situation where the AIS data being received shows repeating values of heading, speed or course over ground in illogical circumstances for more than two hours, then this is a red flag and requires further checks.

If a vessel is berthed, the data will inevitably repeat because the ship is stopped. This would be a logical circumstance.

Source: Seasearcher

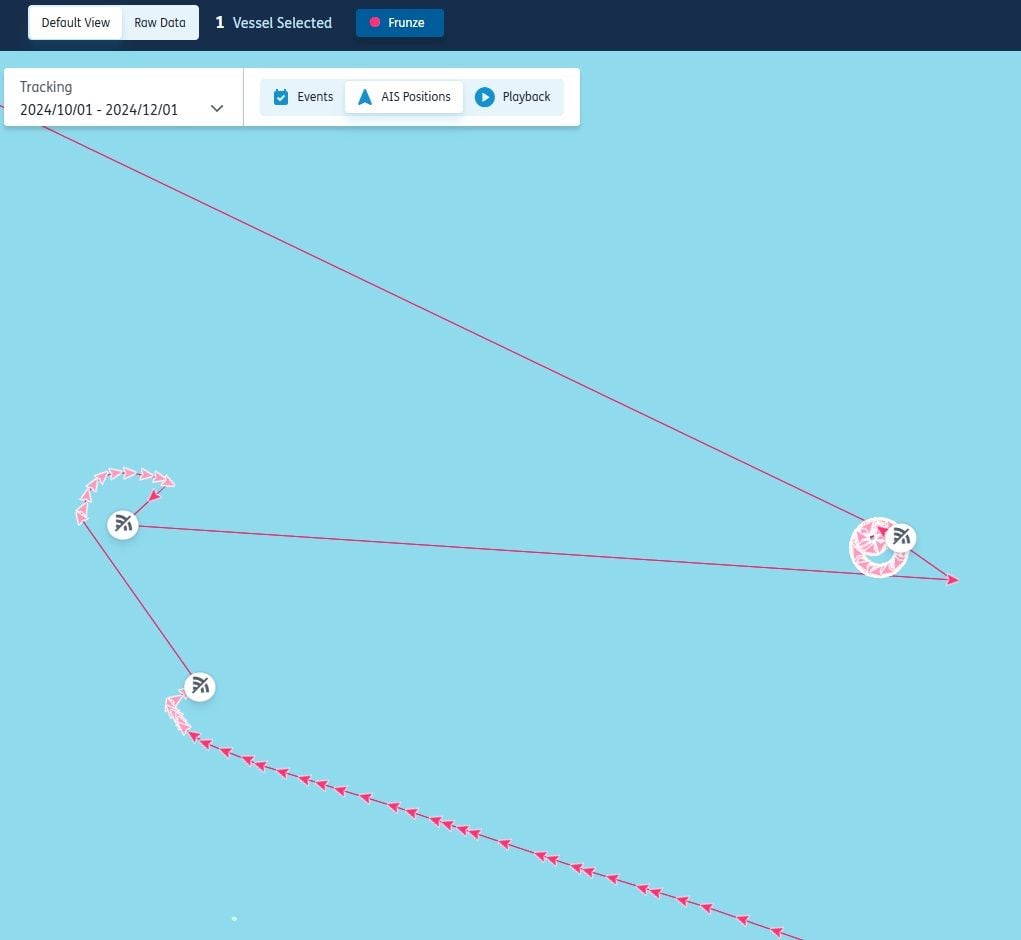

Certain visual patterns are telltale signs of spoofing. One of these is the so-called “box pattern”.

It is easy to overlook this behaviour if you are quickly reviewing AIS positions, so it’s important to review in greater detail instances when ships are stopped.

This is particularly needed in loading hotspots for sanctioned or illicit cargos, including ship-to-ship areas, or when ships appear to be extremely still in common spoofing locations such as the Middle East Gulf.

The image below is an example of a ‘box pattern’:

Source: Seasearcher

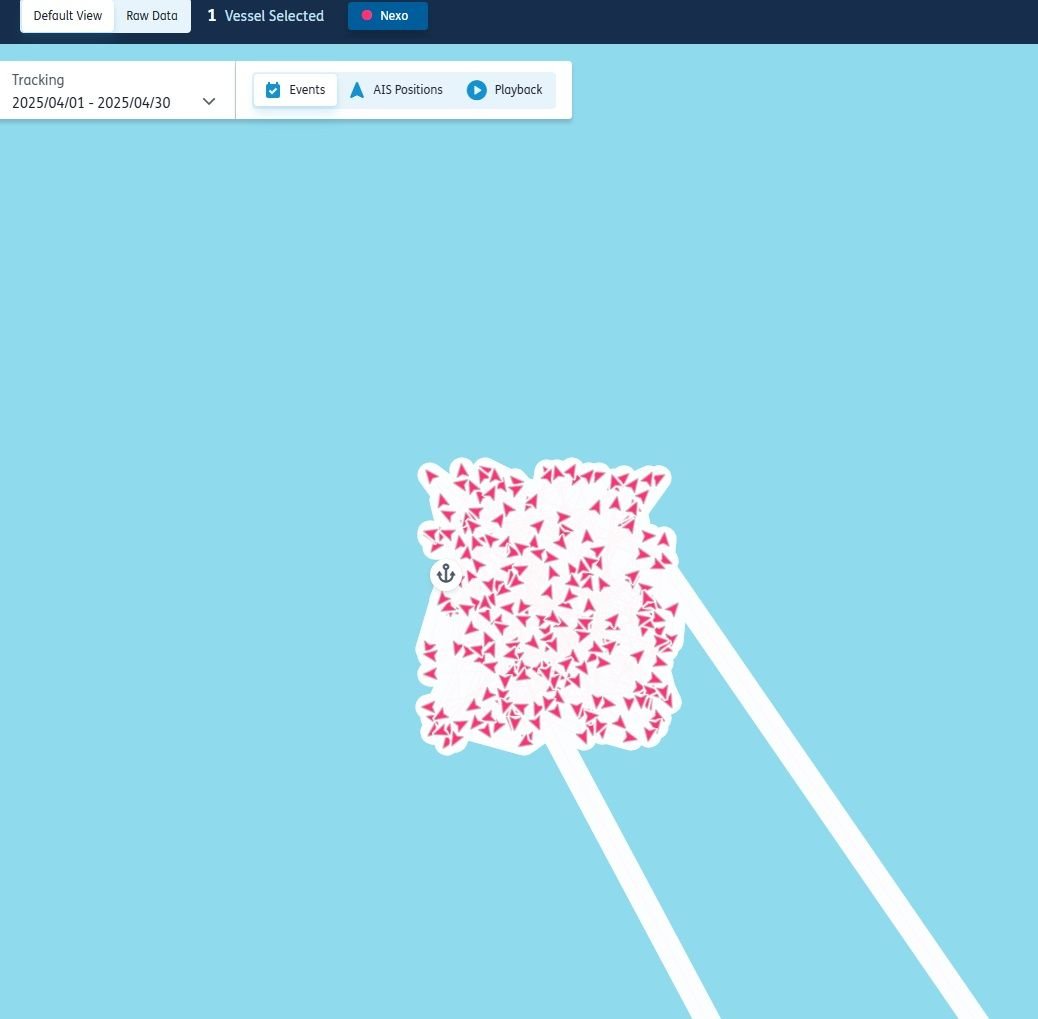

The image below is what the vessel’s voyage looks like at a high level. The spoofing event is happening at the northernmost point of the AIS trace.

Source: Seasearcher

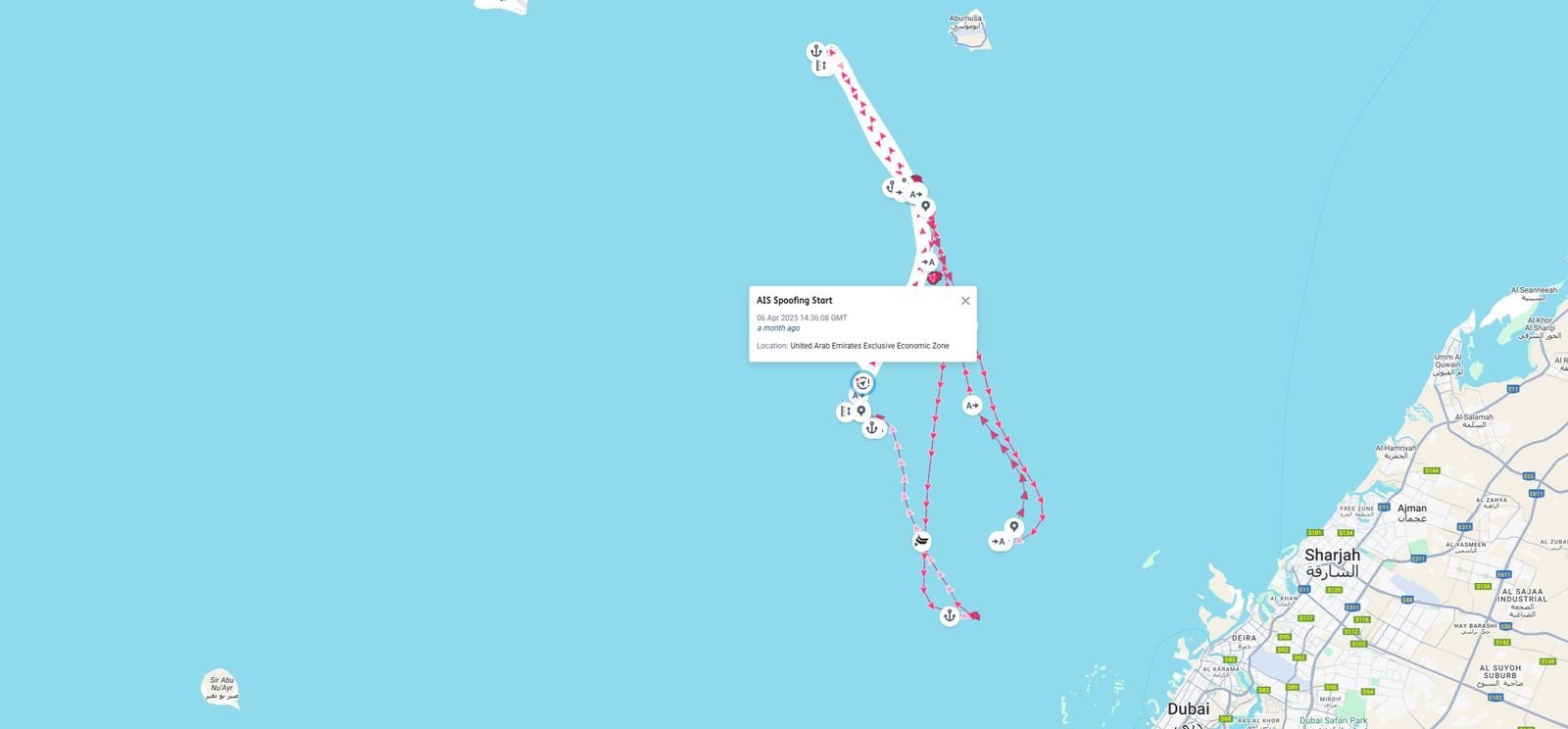

One of the easier forms of spoofing to recognise is when ships move in pristine geometric patterns, such as circles, as this is impossible to achieve in real life.

Below is a zoomed in view of a vessel spoofing itself into a geometric pattern, in this case a circle.

Source: Seasearcher

The AIS trace at a higher-level can be seen below, for context:

Source: Seasearcher

Spoofing has become increasingly complicated and sophisticated over the years as increased regulatory scrutiny has demanded more innovative ways to avoid detection.

A typology that is difficult to detect without granular data or additional resources is spoofing that mimics normal AIS trails.

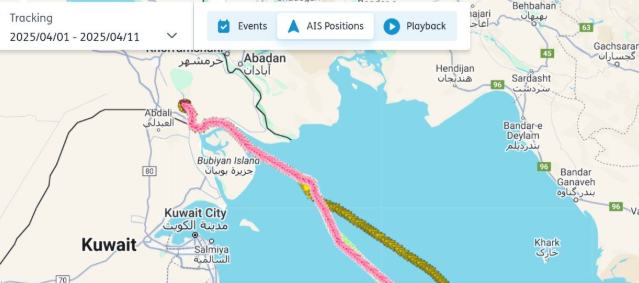

This can be seen with Iran-trading liquefied petroleum gas carriers. Their AIS data shows them calling Iraq, but in reality, they are most likely loading in Iran.

A Lloyd’s List analysis found that more than 60% of LPG carrier port calls in Khor al Zubair, Iraq, between January 2024 and February 2025 were likely manipulated.

The issue is so prevalent that at times, two or more vessels appear to be loading at the same berth simultaneously.

For instance, on April 11, 2025, four LPG carriers can be seen on AIS in Khor al Zubair, including three at the same berth. Yet satellite imagery shows only one vessel there, indicating the remaining three were spoofing the AIS.

Source: Seasearcher

AIS tracks are not a good red flag in this instance as the voyages mimic normal sailing behaviours.

Source: Seasearcher

This form of spoofing has also been observed with tankers pretending to call Khor al Zubair’s oil terminals, located several miles north of the LPG complex.

A look at the three spoofers’ AIS trails as they enter the port shows nothing out of the ordinary, illustrating the increasing sophistication of spoofing.

However, gaps and irregularities sometimes do occur during this specific type of spoofed voyages, likely when the vessels switch between genuine AIS and manipulated AIS.

This highlights the importance of thoroughly checking both positions and the data transmitted through AIS.

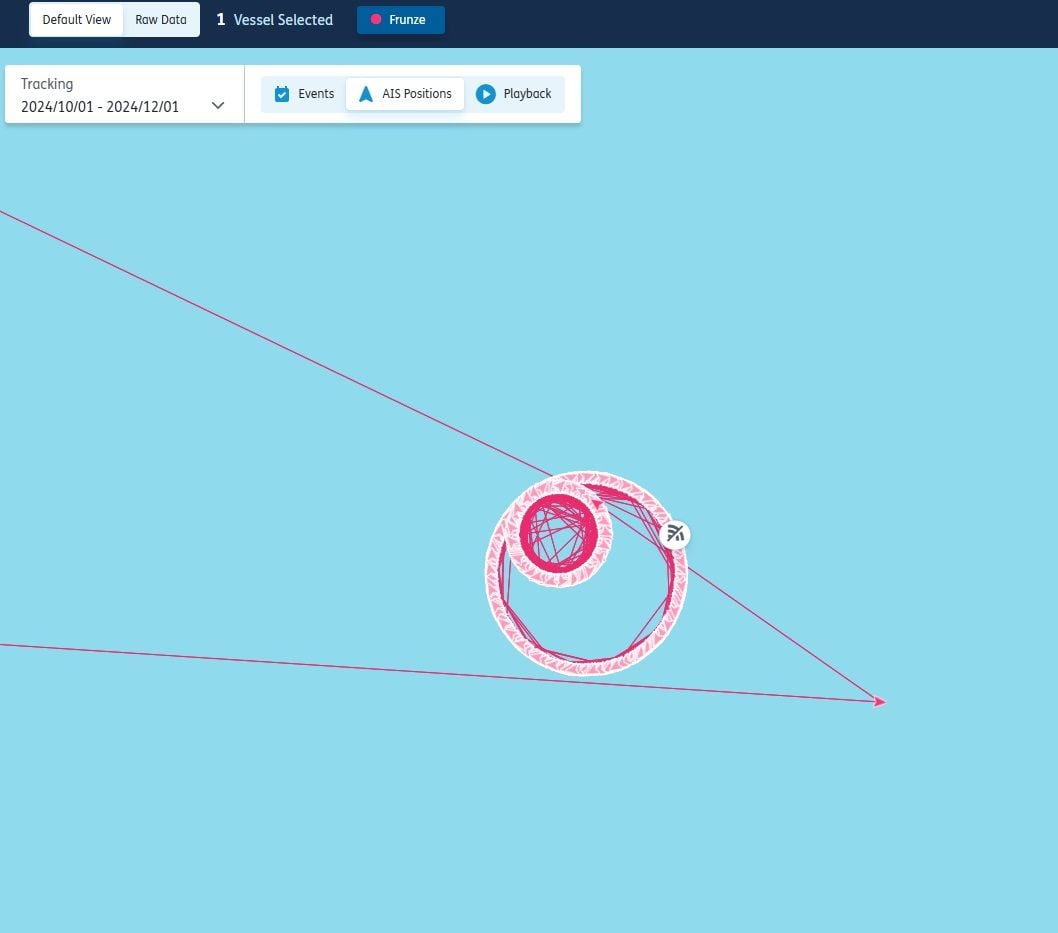

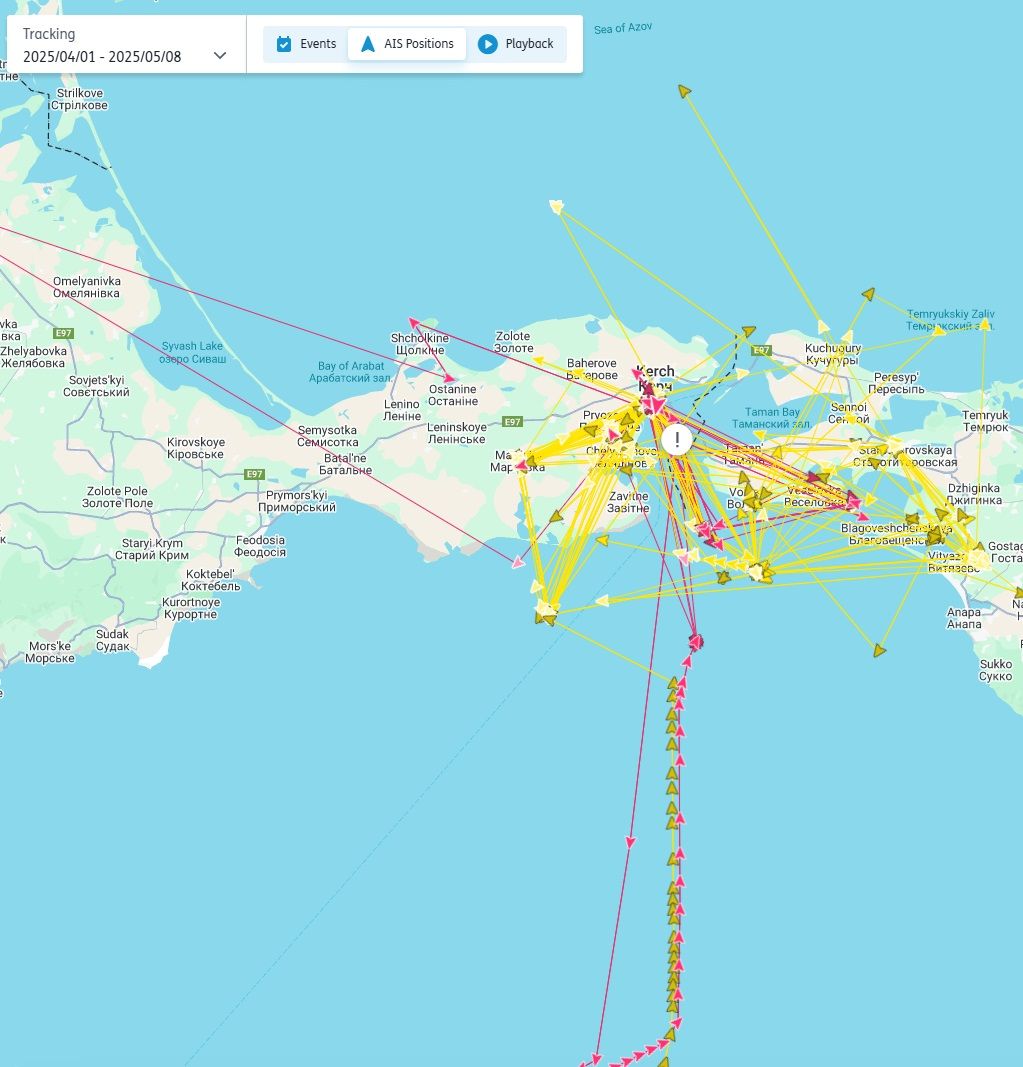

The random and unusual positions seen in the image below are illegitimate. However, it is not people on the ship or anyone affiliated with the ship that is manipulating the information, rather this is the outcome of third-party disruptions.

Source: Seasearcher

Identifying first-party spoofing can be tricky if you do not know what to look for.

It is becoming increasingly difficult, even for practised spoofing spotters, to accurately recognise these events because of a rise in third-party interference.

This is when a third party disrupts the Global Navigation Satellite System receivers on which AIS systems rely to derive positional information, thereby manipulating the coordinates a vessel transmits via AIS.

This type of disruption happens most commonly in conflict zones and the disruption to AIS is understood to be an unintended consequence of this activity.

Importantly, third-party interference typically impacts all vessels in a certain area indiscriminately.

Like first-party spoofing, though, the location data received for vessels is illogical or impossible.

Sometimes it is straightforward to distinguish first-party spoofing from third-party interference, as the latter looks more erratic, as seen in the image above.

To distinguish between the two you must leverage a key characteristic of third-party disruptions: all vessels in a certain area are impacted indiscriminately.

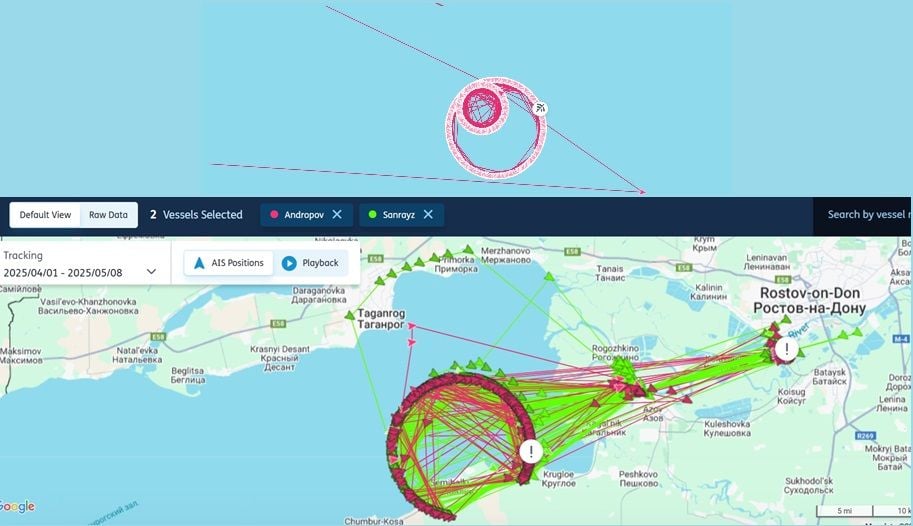

The top image below is first-party spoofing, whereas the bottom image is third-party interference.

Source: Seasearcher

However, over the past year, the third-party interference has evolved and the impact to vessels strongly resembles the patterns seen in first-party spoofing.

This puts additional pressure on risk and compliance professionals as they must accurately distinguish between first-party spoofing and third-party interference because — in the case of the latter — the impacted ships are victims of spoofing, rather than being the perpetrators.

In these situations, the best course of action is to assess the behaviour of the vessels suspected of being in the same vicinity as the target vessel.

If it is the case that all vessels within one area — typically the area before the location data became disrupted — are behaving in similar ways and having their positional data spoofed to the same locations or in a similar manner, then this is more likely third-party disruption than first-party spoofing.

Third-party disruptions can occur almost anywhere, but today it happens most intensely and frequently in the Black Sea and Sea of Azov, around Russian ports in the Baltic and Arctic, and off Sudan.

For more information on how our solutions can help your business navigate the evolving threat of spoofing, visit https://www.lloydslistintelligence.com/risk-evaluation